-

Military leadership seen to be taking lead in critical domains of foreign and security policies while Elected Government appearing as a junior partner

-

Federal Government appears unable to institutionalize consultative decision-making process, whether civil-military or civil-civil, on matters of national security, as fora for institutionalized consultation such as the NSC and the Cabinet remain dormant

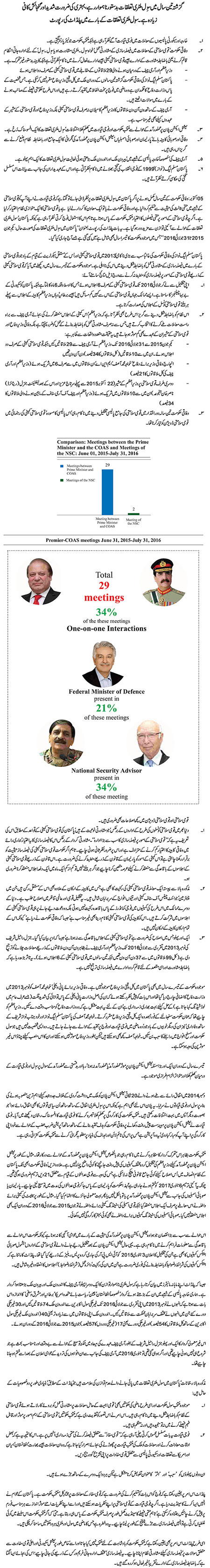

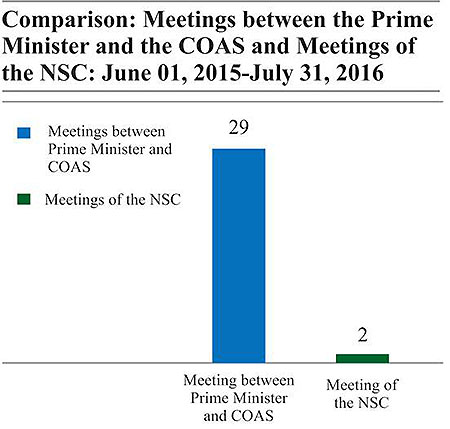

- In comparison to 29 meetings between the PM and COAS for June 2015-July 2016, only two meetings of the NSC held

- PMLN-led federal government fails to appoint a full-time Defence Minister in the country for the last 3 years; The person holding charge for Defence Ministry criticised military in strong language in the past and thus raises question on government’s judgment

- Prime Minister’s penchant for one-on-one meetings with the COAS have not only undermined the NSC, but also the offices of Federal Minister of Defence and the National Security Advisor

-

Public disagreements between the elected Government and Military leadership on implementation of National Action Plan are an unfortunate dimension of civil-military relations

-

Federal and Provincial Cabinets, Parliament and Provincial Assemblies have shied away from developing robust and periodic oversight of implementation of NAP

-

Growing profile of the COAS, especially in foreign-policy domains, both at home and internationally, another dimension of civil-military relations

-

PML-N appears to have failed in overcoming the bitterness of 1999 coup and statements of its officials continue to reflect the continuing bitterness.

October 05; Looking at civil-military relations in Pakistan as the Federal Government completes three years in office, it appears as if the Military leadership has established itself as the final arbiter on national security, with the Elected Government relegated to either an auxiliary role, or a parallel national security regime. Although the mandate for final decisions on national security resides with the elected government, it is seen to be exercised by the Military, as Pakistan moves further away from a constitutional equation on civil-military relations. This was remarked by PILDAT in its Report titled State of Civil-Military Relations in Pakistan, June 01, 2015-July 31, 2016, including the 3rd Year of the current Government, which was released today.

Perhaps the PML-N-led Federal Government’s biggest failure has been its inability to institutionalize a consultative decision-making process on national security despite the creation of the National Security Committee (NSC) in 2013 complete with a permanent secretariat. The 3rd year of the current Government shows that just the lack of institutionalisation of national security decision making through the National Security Committee has resulted in the following:

- Since its creation, the NSC has only met 6 times till July 2016, with a dismal periodicity of six months, even though Pakistan has had more than its fair share of security-related challenges. In countries with far less serious national security crises, such as the United Kingdom, Prime Minister chairs weekly meetings of the National Security Council, before the Cabinet meeting.

- To further compound this aversion to institutionalization,

the Prime Minister has instead chosen to interact directly with the Chief

of Army Staff, which has not only undermined the entire process of institutionalised

consultation but also the office of the Federal Minister of Defence as

well as the National Security Advisors. The bitted reality is evident

in numbers:

- From June 01, 2015 to July 31, 2016, the Premier met the COAS 29 times while only two meetings of the NSC were held; 10 of these meetings (i.e. 34% of the total times they met) were one-on-one interactions

- Federal Minister incharge for Defence, Khawaja Muhammad Asif, MNA, was present in only 6 of these meetings (21% of the total times the Prime Minister and the COAS met)

- On the other hand, the National Security Advisor to the Prime Minister (before October 22, 2015, Mr. Sartaj Aziz, and then Lt. Gen. (Retd.) Nasser Khan Janjua) was present in 10 of these meetings (34% of the total meetings held between the Prime Minister and the COAS)

- Failure to formulate a comprehensive National Security Policy in 3 years in office; the policy was to be drafted by the National Security Division, under the guidance of the NSC

The NSC requires certain reforms as well:

- Pakistan’s National Security Committee, unlike its equivalent institutions of National Security Councils the world over which are only consultative in nature, is defined as per its rules as the country’s ‘principal decision-making body on matters of national security’. This, decion-making power, as opposed to a consultative role, in our view, undercuts the authority of the Federal Cabinet and must be revised. If, however, the Government wishes to retain the decision-making status of the NSC, in our view, an Act of Parliament is required to regulate the workings of the NSC. This act should also set regular periodicity of NSC meetings to be at least once a month if not weekly.

- Linked to the above is the membership of the NSC, which has non-Federal Cabinet members as its full-time members, including Chairman Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee (CJCSC) and the three Services Chiefs. This composition is an anomaly both nationally and internationally where military commanders do not have membership positions but join NSC meetings upon invitations. Labelling the forum as the National Security Committee of the Cabinet, as the current Government has done so with membership to non-cabinet members, is inappropriate in this respect.

- Perhaps another aspect requiring improvement is the infrequency of NSC meetings. As shared above, the Prime Minister and COAS have apparently preferred doing business through one-on-one meetings since Gen. Raheel Sharif’s appointment in November 2013 till July 2016 (of a total of 99 meetings, 37 were held as one-on-one interactions versus 6 meetings of NSC in 3 years). It increasingly appears that official consultation and institutionalised decision-making at the officially designated forum is not a priority.

Pakistan continued without a full-time Defence Minister even during the third year of the current government. Khawaja Asif, the federal minister for water and power, was given the additional charge for the Ministry of Defence in November 2013 and given the heavy agenda his original ministry of water and power carries to solve the electric power shortage crisis (commonly referred to as ‘Load Shedding’), it is hardly plausible that he can devote a decent amount of time to Ministry of Defence. Prime Minister should have appointed a full time Defence Minister soon after assuming charge of the government. Despite Khawaja Asif’s loyalty to PMLN and Mr. Nawaz Sharif personally and despite his other qualities, he carries a baggage of criticising the military leadership and the institution of the army. He is hardly the person to build bridges between the civilian government and the armed forces. Khawaja Asif has been anything but effective as the Defence Minister and the choice of his person may also have contributed to this ineffectiveness.

Another major issue during the 3rd year has been that of effective implementation, or lack thereof, of the National Action Plan (NAP) and rather unfortunate open and repeated finger-pointing between the civil and military leadership as on the question of its implementation.

The 20-point NAP, agreed upon in December 2014 is hailed, both by the civil and military leadership, as the most important road map for the struggle against terrorism in the country. The NAP is also significant because it has the rare consensus of otherwise bitterly opposed political forces besides the civil-military agreement. The Military leadership has shown an unfortunate inclination to sit publically in judgment of the performance of the Elected Government. While the Military leadership was quick to point out the Federal Government’s alleged lagging performance on the NAP, it congratulated its own performance with regards to Operation Zarb-e-Azb, an operation that also sees the elected Government shying away from the required oversight based on targeted objectives and timeline of Zarb-e-Azb .

The Elected Government appears to be unable to display the proactive leadership that is particularly required with regards to the implementation of the NAP. For example, there is no clear indication of the progress achieved by the various Committees formed by the Prime Minister to implement the NAP. Additionally, the Federal Government has also not till yet brought a comprehensive legal package to reform Pakistan’s justice system, which necessitated the 21st Constitutional Amendment leading to the formation of Military Courts. As the Constitutional Amendment is set to expire on January 06, 2017, the Government may go back to the parliament and seek extension of the Military Courts. None or negligible legislative periodic oversight has been exercised by the Parliament and Provincial Assemblies on the implementation of the NAP. For example, the Senate’s Committee on Interior has convened only a single meeting on the issue, whereas the National Assembly’s Standing Committee on Interior was unable to convene a meeting on it even once during June 2015-July 2016. Provincial Assemblies standing committees on home affairs also did not do any better.

More than anything, the biggest loss has been of the public’s knowledge on the status of the implementation of the NAP, as the Government has been unable to share regular updates in this regard. The same is true of the national security institutional structures devised after the NAP, including the Provincial Apex Committees, whose formation was announced through an ISPR Press Release on January 03, 2015. PILDAT believes that there is an urgent need to formalize the terms of reference of the Apex Committees, including their membership, scope of work (Terms of Reference), periodicity of meetings, etc.

As PILDAT has been noting in its monthly monitors, another aspect of the lopsided civil-military equation has been the growing profile of the COAS, both at home and internationally. His growing outreach in certain domains of our foreign policy, especially vis-à-vis Afghanistan, China, United States of America, United Kingdom and the Middle East is reflected in 74 in-country meetings with foreign civilian dignitaries and 30 visits abroad where he also interacted with different heads of state since his appointment in November 2013 till July 2016. The bulk of his in-country meetings, i.e. 40 (54% of his total in-country meetings with civilian foreign dignitaries) and foreign visits, i.e., 17 (57% of the total of his foreign visits) have come between June 2015-July 2016.

Another dimension of this unusual profile is the untimely and inappropriate debate surrounding the possible extension in the term of Gen. Raheel Sharif as COAS, which should have never even been initiated but certainly should have been laid to rest with the COAS’ public announcement denying such rumours in January 2016.

The aforementioned trends are symptomatic of a larger malaise facing civil-military relations in Pakistan, which PILDAT believes can be primarily defined by two characteristics:

- The Civilian Elected Government at present, and similar governments in the past, have failed to institutionalize national security management by institutionalising a consultative process on vital national strategic issues. This has strengthened the perception that elected governments are neither serious nor methodical in making well-considered decisions on vital national security issues.

- The Military leadership continues to feel that the final

onus of deciding ‘national interest’ is on them. As a result,

at times, instead of giving their input and then leaving the matter to

the elected leadership of the country, insist